EPISODE SUMMARY

In part one of our Best Practices episode, we took a look at strategies for building strong partnerships and for a successful roll-out. In this final episode, we’re picking up where we left off. We explore San Francisco’s best practices in gaining trust with their outreach strategies; go in-depth with Seattle’s excellent education program; demonstrate the hands-on tracking system in Los Angeles; and discuss key policy measures that can impact a program’s success.

Links to other episodes in the Series:

Episode 1

Episode 2

Episode 3

Episode 4

MADE POSSIBLE BY STREAMSORT

Streamsort is a data collection tool designed for quick, easy and accurate material characterisation studies and analysis in the waste management sector. The use of data today is still based on archaic methods of collection and analysis. Streamsort brings data collection technology to the next level, by removing the cost of data entry, reducing the risk for mistakes, and making compelling and analysing data much easier. Request a free demo on www.streamsort.com.

FEATURED EVENTS

The International Compost Roundtable, a side-event of the COP21 Climate Conference. December 4th, 2015. 14:45-18:30. Le Bourget, Paris.

This event will bring together leading practitioners, cutting-edge researchers, and Global South representatives of local farming and cooperatives of waste pickers to look into the climate solutions around organic waste, particularly exploring the intersection between zero waste and agroecology. In cities around the world, practice is showing that tackling organic waste is key; while being part of the problem, its proper management in composting can turn it into a real solution for soil depletion, emission reduction from landfills and use of chemical fertilizers.

COMPOST 2016. January 25th to 28th, 2016. Hyatt Regency – Jacksonville, Florida, USA. Organised by the United States Composting Council.

Join the USCC at the world’s largest composting conference and exhibition for the organics management industry. Hear the latest from industry leaders about solving challenges in collecting organics, manufacturing and using compost, and producing renewable energy from organics. Visit their composting tradeshow to see the latest in equipment and tools for effective programs. of particular interest to listeners of this program will be the Session on Measuring Diversion Improvements from Enhanced Tenant Engagement at Multi-Family Dwellings, presented by Lily Kelly of Global Green.

EPISODE SLIDESHOW

Main picture by Stefan Oh. Some rights reserved.

Transcript:

CHAPTER 5: DOOR-TO-DOOR OUTREACH STRATEGIES AND LOBBY EVENTS

THE ORGANIC STREAM: We left off episode three discussing Milan’s outreach campaign as part of their roll-out strategy. One of the key ingredients of their campaign was meeting tenants face-to-face in the apartment buildings, or at community meetings. This is the cornerstone of any outreach campaign.

I want to look at this in a little more detail, because engaging tenants is not always as simple as just heading over to the building and knocking on the door. It’s about gaining trust.

In episode two, we discussed in detail the importance of understanding the demographics you’re working with – reaching people where they are – either online or offline, at community gatherings, social media spaces, television, on the street at local festivals, and so on. Also making sure to have native speakers of the different languages on staff is crucial. This can go a long way to getting people to engage and to trust you. But there is more to it than that. Program coordinators have a few extra tricks up their sleeves to get people in apartment buildings interested, engaged, and willing to attend meetings.

Remember Alexa Kielty, member of the residential zero waste team at the San Francisco Department of Environment?

Well, Alexa told me a lot about their outreach work, and I was really impressed. We covered San Francisco in great detail in episode one and two, and as we know their zero waste strategy is one of the most impressive zero waste initiatives. In terms of organics recycling in multi story buildings – all residential buildings with less than six units separate their organics, and eighty percent of large-scale residential buildings do the same. Right now, San Francisco is focusing on the remaining twenty percent to close the gap, and because of this they have started to really hone-in their outreach strategy.

Alexa told me that in San Francisco, staff work directly with building managers to create individualised outreach program for the building – again, this means working with different demographics, customising the outreach materials, and so on. They also go door-to-door to deliver kitchen caddies and outreach materials year in, year out. Because of this, they have some great experience in knowing what to do to gain people’s trust and make it work…

ALEXA KEITLY: After we set up the programs, we have a whole outreach team called Environment Now, which is a green careers program – so, somewhat of a job training program. We hire from the community so we get a lot of native Spanish speakers, native Chinese speakers; we have a native Russian speaker and a native Filipino speaker on staff. And those folks will do what we call a Green Apartments, which is essentially door-to-door outreach within apartment buildings, at about five to seven pm in the evening, so hopefully we’re getting people when they’re coming back from work. And we work with the property manager so the tenants know ahead of time that we’ll be there on the certain days; we find out what languages are needed; we send outreach materials to property managers to post within the building ahead of time and in the elevator, so it’s not a surprise visit.

What’s great is if the property manager can come with us when we do outreach, or the resident manager, which is even better because they typically know more tenants. If that person can actually conduct the door-to-door outreach with us that’s really helpful because more people are willing to open their doors if there’s somebody they know.

TOS: This is great information here. First off, it seems the most important thing is to make the outreach personal. Alexa says they hire people from within the community they’re reaching out to – people who understand the community and are native speakers of the language of that community. It’s easier to open your door to people familiar to you.

Another thing they do is work with the building manager to give people notice that they’ll be coming, of course.

And finally, and most importantly, the trick to getting people to open their doors is to have a building or resident manager come with them. When we spoke to Lily Kelly of Global Green in her office in San Francisco, she said a similar thing…

LILLY KELLY: Having a tenant or a property manager come with us when we were doing the door-to-door outreach initially, especially if it’s a tenant who knows other people in the building, I think we got a lot more people answering their doors because it was their neighbour who’s knocking and saying, “Hey I want to introduce you to this person who’s doing this composting project, we’re going to have this at our building and it’s going to be really great”. I think that really changed people’s perspectives on it right at the outset of, “Oh, this is something my neighbours are interested in.

TOS: Gaining trust is a big part of getting people involved and interested in the program. So if tenants can see there’s someone from their building that’s interested, they might be more inclined to listen.

Now, in a big city, with a lot of buildings it’s not always easy to manage or finance such initiatives – which is why it’s a good idea to find recycling champions in the building – either a tenant or building manager and support them in promoting the program. Seattle has a great volunteer program for building managers that does exactly that, the Friends of Recycling and Composting program – and I’ll get into it later in the episode.

Another great tactic is to work with people that have some social significance – popular figures within the community, or local celebrities. This can really boost a program’s image and make it more attractive.

So that’s door-to-door outreach. Now let’s look at open events, or what are often called lobby events.

Setting up an event in the building, where people can come along to get information and perhaps pick up equipment is a common strategy. Many programs do this, and it can work quite well. But to get people to take time out of their day to attend, that requires some strategic thinking.

There are two main tricks you can use that have been shown to give results. And to learn about them, I wanted to take a trip back down memory lane, to one of the first interviews I ever did here on The Organic Stream.

(Clip of old episode plays).

TOS: This is our second episode, when I interviewed Rokiah Yaman and Clare Brass, director of the SEED Foundation, about her food scrap recycling research program that aimed to discover the barriers to organics recycling in urban environments. Clare was working with an inner-city estate, the Maiden Lane estates, in a disadvantaged area in London. And she told me about her difficulties in engaging the residents, who had much more immediate problems to deal with.

But using some clever techniques, she was able to overcome these challenges and get people participating in the program anyway.

CLARE BRASS: Recruitment is still the most difficult thing with these projects and you need to get under the skin of the people, your primary stakeholders. Now, often the thing that is driving you, so in our case the environmental challenge of food waste, is not the thing at all which is maybe driving a resident of a housing estate.

The thing that works quite well, and I think this is a really good trick, is that we piggybacked on an event that was happening at the estate. Just when we started the project there was a barbeque event coming up on the estate. We went along to that event, and we set up a stall with a poster. All we did really was go along with a whole stall full of little tomato plants, a bucket of food waste and a bucket of compost, and just talked to people and say “did you know that your food waste can look like this one day, and then it turns into this?” And most people were quite surprised, but it was an opportunity for us to start a conversation with them.

And I think the key thing here is, if you’re recruiting, it’s to go to where people are already going to be going, and just give them a little, a little tiny reward. Just to have a first point of contact. After that we managed to get about 15 to come to our first workshop. So that was a really good way in.

TOS: So there we have two of the best strategies for getting people to attend – using existing meetings or events at a building for your own outreach event, and make sure to have rewards. Other programs, such as Seattle, often advertise their educational presentation sessions in buildings as the place where people can collect their free containers. Another really great idea is to provide refreshments, because as program managers have told me – people tend to come if there’s food. So these strategies work really well.

CHAPTER 6: FOOD SCRAP COLLECTION EDUCATION STRATEGIES – SEATTLE CASE STUDY

TOS: One of the most important goals of an organics recycling program is to change behaviour and to get people to understand the impact their actions will have. Without this, there is no will to carry out the action. And this is where education comes in.

We touched on education before in episode two – focusing strongly on the importance of multi-language education materials.

Today, we go further and focus on the excellent education strategy that Marcia Rutan, Recycling Program Manager at Seattle Public Utilities, employs for their organics program.

TOS: Marcia Rutan has been working in education for a long time and she’s been greatly supported in her work thanks to Seattle’s progressive recycling laws. We learned quite a bit about Seattle’s organics program in the last episode. In 2011 it became mandatory to provide organic carts in multistory buildings, and implemented a full composting mandate for the whole city in January this year. Fines for too much food waste in garbage containers will start to be issued in January 2016.

From researching their program, I was inspired by the work they do to educating people. When I got Marcia on the phone, I wanted her to tell me all about it. And the first thing I asked was to start from the beginning: just what were the basic building blocks of their educational program?

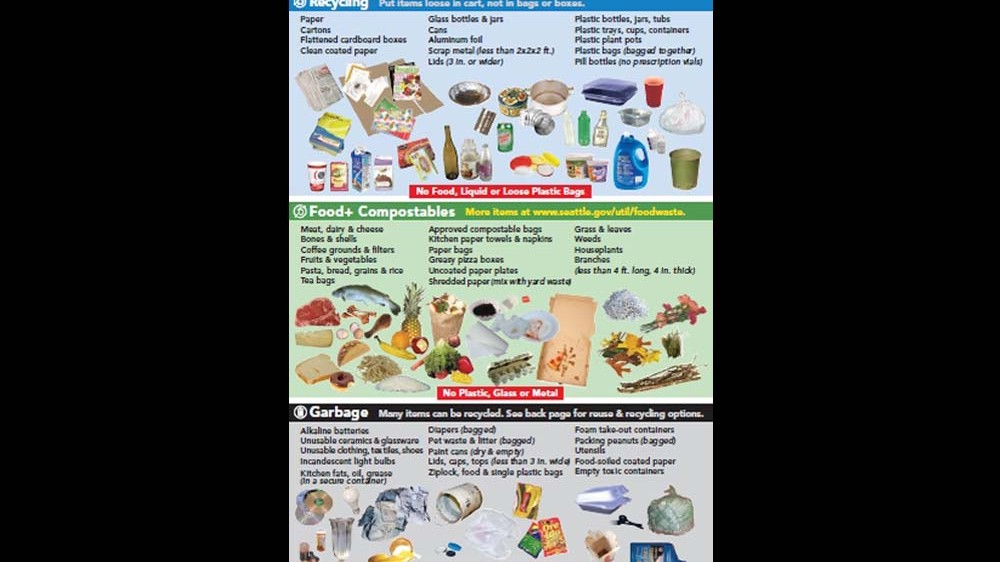

MARCIA RUTAN: In terms of education, what we find across the board is that property managers especially appreciate posters that can be placed above the carts. Then we also have labels for the carts, and all of these have pictures as well as wording. And then we have our basic flyers. We use two basic flyers for this program. One is called the Where Does It Go flyer, and it has colour coding for all three waste streams: the recycling, which is blue, the compostables, which are green, and the garbage, which is a grey/black colour. The other flyer then is basically a food plus compostables guideline, which is all green, and it’s just to make it clearer to people what goes into the compost cart since it’s a new program. The flyer also provides a few “why is this important” points, as well as tips for storing and carrying out materials – so it just gives some more information. Those are the two basic flyers that we use with this program.

These are foundational for the property managers. They really rely on those flyers, the labels, the posters and the carts – and they’re all colour coded. And that partly came from…in about 2007 or 2008, we held focus groups with community based organisations. They were primarily constituted of folks who were immigrants or who have English as another language (I won’t say second language, because we know some of these folks have several languages under their belts). But they said they wanted the colour coding, and they didn’t want a “yes” “no” type of poster, which was confusing to them, but just “where do things go” in all categories. So that’s where these informational flyers came out of, and the colour coding.

TOS: So flyers, labels and posters are foundational elements for property managers in Seattle. Using focus groups to understand what residents would prefer gave them a better idea of how to design their materials. Colour coding is a crucial element – many cities agree that this is key. It’s easy to understand and transcends any language barriers as well. Another important element that also overcomes language barriers, and for those with reading difficulties, is pictures. And it was Alexa that said to me at one point during our interview that a lot of people, no matter what language they speak, tend not to read the posters – so pictures can really help.

One important thing here I want to bring up is the design of the materials. We often see too many design mistakes – so materials are either overcrowded with information and pictures, the signage is unclear or hard to follow, colours and contrast is also something to take into account as well, because if there is too much going on, or it’s just plain black and white, people won’t want to look at it. The more well-designed, clear and pleasant to look at the materials are, the better it will be.

So – educational tools such as flyers, hand-outs and stickers can be classed as passive education tools. Other very popular passive education tools are promotional tools like door hangers or magnets, and of course websites, apps, and social media.

Now, Marcia mentioned websites and social media as tools they like to use for education and outreach – and this was the same for all the cities we interviewed. In this day and age, when so many of us rely on smartphones and the internet as a primary source of information, having an online presence can make a big difference. The benefits are great. They allow program managers to interact directly with residents, share information quickly and easily, and to answer questions.

There are an increasing amount of platforms online to use to get the message out. The key here is to choose the right platform for your target group – for example, younger generations don’t tend to use Facebook as much as they use Snapchat or Instagram. The DSNY in New York have currently started an Instagram account, to try and reach the younger audience – they also have twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Flickr accounts. So there are a growing number of platforms, and when designing your outreach strategy, it is your responsibility to adapt your strategy.

So these are great passive tools to use in an educational campaign. But what about the more hands-on approach we discussed before?

What interested me greatly in Seattle city as a case study and Marcia’s approach was her use of a more active educational approach. At many of the properties, Marcia conducts one-to-one on-site presentations that seem to go down very well with the residents.

MR: And we use that Where Does It Go flyer and we take props with us so people get a hands-on experience with putting things into the right colour bin. So I take two big bags of stuff, I distribute it to folks, teach them how to use the flyer, and then they come and put it into the bin they think it goes in and we discuss it. And this is a very popular game, people really love it. I’m a real believer in multiple educational intelligences: rather than just looking at a printed form, that people get their hands on things, and are kinaesthetic as well – they like to get up and move. So I think all of those are really important.

TOS: This idea of providing a mix of different educational methods to help reach people is an interesting one. And practicing the physical act of putting organics in the right bin can definitely help make the lesson to stick in a person’s mind.

With on-site presentations like these, it’s easy to see how they can help build a positive relationship between tenants and the program. It also gives educators a chance to get feedback directly from people, address questions and so on.

Seattle has 5 thousand multistory properties…and half of the population of the city lives in mulitstory buildings. That is a lot of people to reach out to. I asked Marcia if they had the budget to be able to reach everyone this way, and she said no. But what they do have is the volunteer program that I mentioned before…

MR: We run a train the trainer program called Friends of Recycling and Composting, where property managers or their designanted representatives come and take a two-hour training to get motivated and educated on where does stuff go and best practices at the property, as well as how to motivate residents. And people provide really high marks on this training program. They say they basically came just to get the free buckets (which we use as a hook to get them there!), but they left actually profoundly motivated to back and work with their residents, so it’s been really effective.

TOS: While it’s important to educate tenants, many reports show that the most effective education is focused on property managers. This is why the Friends of Recycling and Composting Program is such a great tool.

But educating building managers and owners is not without challenges.

MR: There is quite a bit of turnover of property managers, so we’ll just get them educated and inspired, and then they’ll move on to another property…which sometimes can work in our favour, because then they go on to help that other property get going. But sometimes we just basically lose them. And then there’s also resistance by some property managers: they hide the cart, they don’t want the residents to use it because they don’t want to deal with the ick factor, or they perceive a mess is going to happen. So we have missing carts.

We don’t have a good way to deal with the turnover – we just train, train, train and then like I said, some go on to other properties and help out those other properties to get going. But in terms of resistance – the drivers do report missing carts and we can just sort those and find out what are the larger properties (because those are the ones we go after). And then we target them. We give them a call, we go on site and find out what the barrier is for them to participate. Then we work with them, trouble shoot and provide education – anything we can to help feel more confident to get going. And often it’s that they’re very busy, so it can be a time issue. Another issue is fear, and we just try to deal with those fears. So a lot of those have gotten up and going.

TOS: One thing about education is that it’s always on-going. There is no real end to the work that needs to be done. Especially for a city like Seattle – with a program that’s very comprehensive and can still cause confusion over what goes where. We gained a lot of insight into what tools work best for educating both tenants and property managers. But the most inspiring thing to take away from the Seattle case study is their commitment to constantly refining their strategy year after year to help clear up this confusion.

MR: We continually listen to our customers. We do have a wonderful “look it up” tool on our website, which is one of the most used links on our website, where hundreds of items are listed and the best disposal practices are provided for, and it’s just so many different materials. So that’s been a big help. And we are also continually listening when people give us feedback about what isn’t working with the flyers, or what might need revision, so each year when we go to revise the flyer, we try to make it more clear and useful for people. You know, it’s not always going to meet everybody’s personal style of education, but we just do our best. We really try to listen to the customer, rather than thinking we’re the experts. We are experts, but we also know that it’s incredibly important to listen to the customer. We learned a lot through the community-based social marketing, we really do employ those principles as much as we can. And so listening to our customers is very key.

CHAPTER 7: TRACKING RESULTS IN YOUR PILOT PROGRAM – LOS ANGELES CASE STUDY

JASON SANDERS: We’re in the Old Bank District Buidling right now, we’re on the eight floor. And we’re walking into the refuse room…and they’re out of compost bags in this one…

TOS: We’re back with Ecosafe Zero Waste’s Jason Sanders and Jessica Aldridge of Athens Services in Los Angeles.

JS: So we have two compost bags in here, and…we do have one aluminium can.

TOS: Here, we’re following them as they conduct their monthly inspections of the trash rooms on every floor of the Old Bank District Building.

JS: We do monthly site visits here to check each floor, and we mark down the odour level, the cleanliness level, contamination level, participation, and what the bag count looks like in the dispenser system.

TOS: Tracking results. This is one of the most valuable tools to have in an organics recycling program – especially a pilot program. The types of information to track can be materials collected, contamination rate, challenges faced, key contacts, and the amount of outreach employed. Compiling a detailed history of all these factors will be invaluable in moving forward, and to give accurate information when presenting program results.

In LA, we were impressed by the strength of their tracking system and their hands-on approach.

JS: So what we’ve seen so far with this program is a high level of participation and a low contamination rate. To this date we’ve done three site visits, and on each of those three site visits we have one or two standard traditional poly bags in the compost bin, and that’s it.

TOS: As you can see, by tracking results in person, Jason and Jessica have a much clearer understanding of how successful their program is. By visiting the building in person, they have a chance to spot problem areas and recognise trends in the buildings.

Of course, one of the most important things to track is the contamination rate. Keeping an eye on how contaminated the stream is, and being able to react quickly to any issues is useful – especially for the processor who will be dealing with the materials on the back end.

JESSICA ALDRIDGE: From the hauler and the collector and processer’s standpoint, we have to make sure that the material we’re collecting is good material. And I would say one of the hardest programs to enact is a multi-family separation program, especially for organics. So through this process we want to keep a very watchful eye on that product to make sure it’s as clean as possible. Because if we’re processing this material and it’s making its way back to our sort line – so, when it comes back to materials recovery facility, we have a sort line that it goes up to and the material that’s not supposed to be in there is pulled off. Then it is shipped off to our compost facility in Victorville, it is screened once again, then it is composted and that compost is then screened once again.

So we want to make sure that we have as little an amount of contaminants as possible, or else we end up with a more strenuous process. And also, it gives us an idea of if we need to send out more education and outreach to the residents here, to the management or to the maintenance – whatever it may be. So that also directs how we’re going to move forward with the program.

TOS: So, tracking is not only is useful to help you to understand and optimise your program, but it can also help shape your program as well. Frequent site visits are an excellent way to keep a close eye on what’s going on and allow you to quickly react to any problems that come up. This is extremely valuable – especially for pilot programs that are looking to expand in the future.

CHAPTER 8: HOW POLICY CAN SHAPE YOUR ORGANICS RECYCLING PROGRAM

TOS: Every organics program is shaped by the regulatory structure it exists within. It can be supported by this structure, or it can be hindered by it. Throughout the show, we’ve come across examples of how policy has impacted on the programs we’ve covered. And it is no coincidence that the cities we chose for our case studies have some of the most progressive laws and policies in place today.

Places that put in place ambitious recycling targets, landfill or incineration diversion goals, or bans on organics going to landfills or incinerators as part of a sustainable waste management strategy are really important. They can create the necessary leverage needed to push for organics recycling. When supported and enforced properly, they can be a critical driver for collection programs. Every city we spoke to has a zero waste vision, or a zero waste commitment, with ambitious recycling targets. Most notably San Francisco – which leads the way in terms of ambitious policy – with just five years to reach zero waste in 2020.

Financial tools used by policy makers to promote organics recycling are important. Pay-as-you-throw systems for waste have been shown to greatly increase participation in recycling schemes in municipalities all around the world. And it makes sense: If buildings are charged more for waste collection than food scrap collection, it gives managers direct financial incentive to participate in the program.

ENZO FAVOINO: Bring systems never work as effectively as kerbside systems do. The true springboard towards zero waste has always been the implementation of a kerbside scheme targeting also the organics. With such a system, you quite easily jump up to seventy or eighty percent separate collection. Then, after that, in order to move further towards one hundred percent, what we do next is the implementation of a pay-as-you-throw scheme. And this increases separate collection by a further ten percent, but also it remarkably decreases the overall waste arisings.

TOS: But in a city where buildings are serviced by private haulers, municipalities can’t always control the price of collection. In some cases, where landfills are publicly owned, they can control how expensive it is to send the waste to these public facilities. Municipalities may also be able to raise tipping fees for garbage, and tax rates for landfilling or incineration, so that recycling once again becomes the more desirable option. This in turn will mean buildings are charged more for garbage collection and give them a reason to start composting!

There are also policy measures that indirectly impact on programs – which we saw in the case of Milan with the ban on chutes and the plastic bag ban that led to biobags becoming more available.

But perhaps what had the greatest impact on the cities we covered are mandates that require composting, or that organics stay out of waste bins.

MARCIA RUTAN: Basically we mentioned the two policies that have been the most critical: one requiring properties to subscribe, which was September 2011 – and that definitely had some impact but it had no enforcement quality to it, so it was not as strong as the new law which started this January that says no food waste in the garbage. And with that associated fine, that has had a very big impact on the properties wanting to participate.

LILY KELLY: When there’s an ordinance, or when there’s a law that requires composting, it really makes a difference. Just listening to the property managers changing their narrative it from, “Oh, I don’t know if I want to compost, it seems gross and smelly,” to, “How do we make this work?”

TOS: While it’s not a fix-all solution, the financial incentives that come with mandatory measures can make a huge difference – nobody wants to pay a penalty for not recycling properly. In multistory buildings, fines that are shared equally among tenants can help combat the anonymity factor. Enforcing these fines work best with a kerbside system.

Those are some of the key policy measures we’ve come across in the cities we’ve covered that have had a direct positive impact on programs. Having a strong policy framework will help steer everyone in the right direction, but it also has another great effect. It leaves program coordinators free to concentrate on doing their job, as opposed to spending their time fighting to change things for the better:

MARCIA RUTAN: Seattle is just a really leading-edge city in this. The agency I worked at previously had a pretty good program, but I always felt like in some ways I had to fight for recycling and composting to continue. Whereas when I’m working with Seattle, I basically feel like I’m swimming as fast as I can to catch up. And it’s wonderful! I can go as fast as I can to do as much as possible and there’s still room for opportunity. It’s really great!

FINAL CONCLUSION

So we’ve come to the end of our show, and it’s been a great journey. We’ve covered a lot of ground on this topic and there is a lot to take in.

But what we’ve seen through this show is that while multi-residential organics programs have their challenges, it is very possible to roll out a well-running, successful scheme.

The success of the programs we covered is a result of careful planning of the system, building strong relationships with key partners, working with building managers to find solutions, spending time with focus-groups to craft a successful outreach campaign, investing in communication, and taking a step-by-step approach to implementation.

They each use a combination of different strategies – all tailored to suit the needs of the specific building, or area, that they’re targeting. Your program’s success is predicated on your ability to execute consistently all the strategies we discussed, and to continually measure and improve your approach as you go along.

And in the case of Milan especially, we can see that with the right system and approach, and a supportive policy to back it up, organics recycling programs in multi-residental buildings can be rolled out with no more difficulty than any other organic recycling scheme.

So while multi story residential buildings can be a challenge for many cities, combining the wealth of experiences and best practices from the leading cities, we have a great roadmap to guide us on our journey.